I've been a GCSE teacher for a number of years now.

In that time I have seen the curriculum we deliver evolve into various

forms that serve our students as best as possible at that particular time.

If I remember back to the first few years of my teaching where I was

under the guidance of a very good former Head of Department, we had the whole

two years mapped out into organised blocks which easily kept me up to date and

on track. At any point in the course I could readily tell you where we

were and what was coming up. The structure was regimented and ensured we

reached the end of the course fully prepped for the exam. There were some

draw backs though. Every lesson was accompanied with a worksheet which

students filled in. It wasn't that inspiring but did ensure that the

theory element remained a strength of the department.

Over the years the curriculum changed. The department began to move away

from the worksheets and began using exercise books. There was more

freedom in the classroom for teachers to teach how they felt best supported

their students. We still remained on track and on target but not for the

reasons you may think. During this transition something had gone missing.

We no longer had a curriculum overview. We seem to have forgotten

to design schemes of work. The experienced teachers in the department

simply used their expertise and excellent team ethic to collaborate and deliver

lessons in an order, working around deadlines and ensuring we fulfilled the

course requirements to as high a standard as possible. We still had a

rough plan and knew what we needed to teach and in what order but nothing was

formally written down.

The aim

Now don't get me wrong, we know this wasn't ideal

but it just seemed to work. The theory element of our results has always

been above national average and our students seemed to succeed. However,

over the last year we have worked hard to address the oversight and implement a

new structure. Working with the amazing Fran Bennett (seriously,

she is an exceptional teacher and colleague!) we have tried to design a

curriculum for our GCSE course that builds upon the great practice going on so

far. The aim of this process was to design a curriculum that both

promoted a very high standard of learning, as well as ensuring students remembered this

knowledge over time.

Leading into this I had been reading more and more

into the field of cognitive science/psychology. What I read

built upon previous work I had come across in my own education (Anderson,

Schmidt, Thorndike etc). As part of the core foundation to the new

curriculum, we would look to implement elements of research into our planning.

These would notably come from the work of Curran, Willingham and Bjork.

Could we design a curriculum in such a way that students could retain

their learning for longer and also reduce the need for intervention in the mad

rush that is exam season?

We also looked very hard at what matters in our

subject and identified areas that should be a priority. Taking into

account what the specification and exam requires is one point, but we also

looked at other components that could truly benefit learning. We didn't

want the curriculum to be too rigid and monotonous. Instead we wanted it

rich with information, meaning and context. We looked to use articles,

case studies, real world experts and so on. The principles needed to be

tight but the day to day use of them needed to allow teachers freedom.

The structure and logistics of the curriculum are also built on some key

fundamental principles revolving around improved levels of writing, refined feedback opportunities, and enhanced levels

of challenge. All of these were based on previous ideas, practice,

experience and research, and allowed us to raise the level of our subject much

higher.

With all of these things in mind, could we be a little bit better at designing a better GCSE curriculum than we previously had?

With all of these things in mind, could we be a little bit better at designing a better GCSE curriculum than we previously had?

The bigger picture - The curriculum overview

It would be wise to point out that at this stage

the overview is a work in progress. We decided to focus solely on

redesigning our Year 9 to Year 10 theory course (omitting Year 11 for the

time being). This was due purely to the fact that we needed to be able to

plan, run and then evaluate the impact of our ideas before rolling it out

further. If it was having a negative effect on outcomes then we would

still have Year 11 to amend it. We also wanted to make the course

manageable and by designing it slowly and carefully we would ensure that what

we were putting into play would be consistent.

As I stated earlier, we have been looking at particular components of effective teaching over the year. The process forced us to undertake a lot of reading of research articles and focus more on evidenced based practice. There were a number of findings that I will explain over a few posts that really challenged our thinking and pushed us into some fantastic discussions. In this post I will talk about how we went about implementing five key findings from the world of cognitive science/psychology into our curriculum design.

Implementing cognitive science principles

Experience over the years has shown me that when

students reach the end of our course they seem to have forgotten chunks of it.

Gaps in their knowledge emerge and worry starts to set in. It seems

that although we taught them the specific content knowledge they need for each

topic, it has somehow become very hard for them to access it. All of the

results, data and anecdotal evidence at that particular time seemed to have

indicated that students knew that information a year ago. The problem is

that a year down the line and this is no longer the case. So is this

performance or learning?

The way we taught our GCSE course meant that

students performed very well during immediate questioning, discussions or

testing. What didn't seem to happen though is the ability to remember

this information later on in the year, or possibly towards the end of the

course. Now there are obviously some students who seem to understand and

remember everything, but there is still a strong majority who forget

information that we were certain was concrete. Some would remember things

when prompted, but there were still a number who had forgotten things taught

nearly two years before.

After a lot of reading of research articles and

publications (summarised here), we were not surprised to find that

although a lot of our teaching was effective in the short term, there were a

number of 'tweaks' that we could make to ensure learning lasted over time.

We began to analyse what we could realistically implement into our first

trial of this new curriculum. Discussions focused around the ideas of

'Desirable Difficulties' from Bjork and general cognitive science principles

from Willingham. So what did we do? What were the cognitive

science/psychology principles we looked at designing our curriculum around?

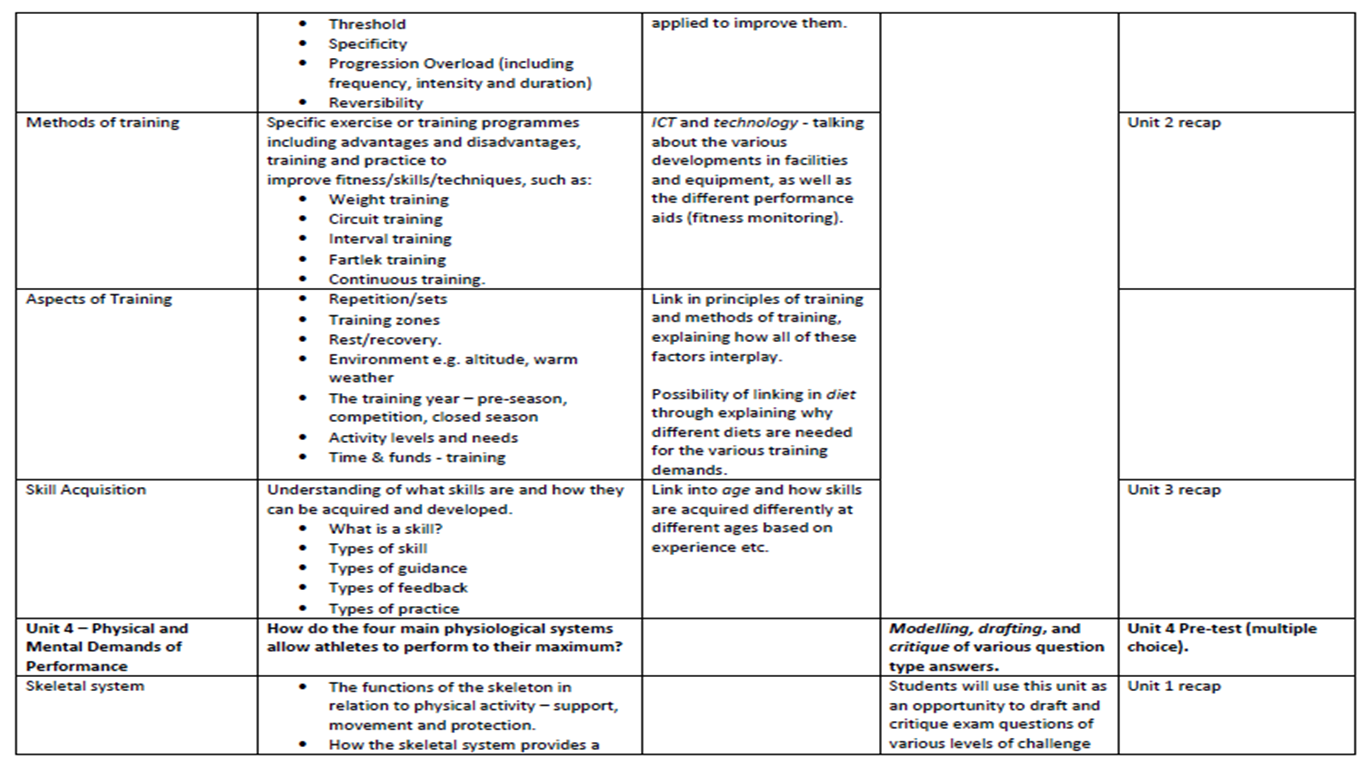

1 - Ordering our units

A number of researchers have stated the point that

knowing things makes it easier to learn new things (apologies for the

oversimplification of this). In designing our new curriculum we built

upon work that had been done previously in the department and ensured the order

of units made sense. We aimed to logistically place units in an order

that built upon the previous units’ information. For example, in Unit 4

we study ‘Physical and Mental Demands of Performance’. The unit covers

topics focusing around the various physiological systems in the body, as well

as some psychological factors as well. As an example, during this topic,

when students learn about the aerobic/anaerobic energy systems, they can draw

upon previous knowledge to help them. Unit 1 information can help them

understand why each individuals system may vary due to age, physique and so

on. Unit 2 can help them see why different types of athletes may have

time to train or even monitor these systems. Unit 3 may help understand

the various training methods that are required to improve either the aerobic or

anaerobic system. The stream of knowledge links.

The aim we tried to incorporate was to build upon prior knowledge so logically ordering what is taught first so it snowballs and draws upon old information. Building upon prior knowledge and learnt information makes learning new topics easier. This is down to the fact that new knowledge being processed in the working memory retrieves and builds upon the older information in the long term memory to form new connections.

The ordering also allowed us to tell the story of

sport and create a bigger picture. Obviously sport is a very complex

domain with a number of interlinking points but we can at least structure the

learning so that it follows an order and makes more sense to students.

The curriculum began with individuals, followed by how they are perceived, how

they raise their performance to succeed and finally what physiological changes

happen during this. This makes it much easier for students to process

this information in a methodical way (and potentially helping reduce the impact

on the working memory and cognitive overload).

2 - Interleaving

I won’t go into detail about the theory of

interleaving as I have written about it here. It is sufficient to say that

cognitive scientists like Willingham and Bjork both agree that if students are

to remember a particular piece of information, they will need to revisit it

numerous times throughout the course. Traditionally we had followed a

method that is referred to as blocking. We would select a unit, teach it,

test for understanding and then move onto the next unit. This provided us

an accurate account of what students knew at that point. What we had done

though is compartmentalised learning. We had isolated groups of topics

into blocks. In the short term, student performance looked good. In

the long term, the result of this is that due to our GCSE starting in May

during Year 9, students in Year 11 struggled to remember back to information

from two years ago. We had not consciously made attempts to recap topics

from earlier points of the course. Therefore we can’t be surprised when

students forget things. Now obviously the more experienced teachers could

make these references when needed, but this was on an ad hoc basis and we

needed to ensure this was done with more thought.

Bjork proposes interleaving as one of the desirable

difficulties that may overcome this. The idea is that topics are repeated

throughout the course so students are forced to constantly retrieve

information. In its most effective form it may include regularly

switching topics and revisiting them repeatedly throughout learning. An

example might be spending time teaching diet in sport, then next lesson

focusing on physique, then focusing on gender and then coming back to diet and

so forth. This also allows students to identify links between topics and

compare information.

In reality though, when we looked at designing the

curriculum this way we found it extremely difficult. I mapped out

(using a spread sheet) all of the topics that we taught, and then attempted to

break up their order so they became constantly repeated. I also tried to

space them effectively so that forgetting came into play. Working with

this system became very confusing and meant that we would run out of curriculum

time very quickly. It is definitely something I will be working on next

year within individual units. Instead, we have tried hard to tie topics

back into new learning so that students have to retrieve that knowledge and in

return increase storage/retrieval strength. For instance, in Unit 4

during the Circulatory system lesson, we have mapped it out that teachers tie

in the Unit 2 topic of ICT in sport looking at measuring heart rate and

training zones. These opportunities are no longer left to chance and are

mapped throughout the entire course. We now have students retrieving various

topics at relevant times throughout the course.

I know it's not mathematically accurate and the

spacing gaps aren't as precise as we would like, but it's hard in reality to

transfer the best principles from research into practice.

3 – Spacing it out

You may have noticed in the point above that I have

mentioned spacing. I explain more about spacing here but it is basically revisiting

information at spaced out times throughout a given period. As Bjork

explains:

"It is common sense that when we want to learn information, we study that information multiple times. The schedules by which we space repetitions can make a huge difference, however, in how well we learn and retain information we study. The spacing effect is the finding that information that is presented repeatedly over spaced intervals is learned much better than information that is repeated without intervals (i.e., massed presentation)"

Bjork also explains that the gaps between revisiting this information is also very important. He suggests that each time we revisit it, the subsequent gap before the next time should increase, and then increase again and so on. The aim it to allow students to almost forget the information. When they come to retrieve it again the strength of it in your long term memory increases.

As I have explained through the process of

interleaving, it was really hard to space topics with the idea of increasing

the spacing between retrieval. How do I know when students are about to

forget something so I can then refer to it? With the spread sheet in hand

I again tried to map out increasing gaps over the year. Again I found

that we would run out of curriculum time in only a few terms. Instead we

decided to group topics together in their units rather than individually.

We also used the natural roll out of the curriculum to increase spacing.

For instance, in Unit 1 we mapped out times you would recover Unit 1

topics. When you get to Unit 2, you would have to revisit Unit 1 and Unit

2 information. When you go all of the way to Unit 4, you would have to

cover Unit 1, Unit 2 and Unit 3 information again. Because there are more

units to revisit, the gap between covering them again increases as well.

4 – Testing that is low stakes but high impact

Traditionally I have not been a great lover of

testing. It would be an option when needed but I didn’t see the full

benefit that it has on learning. Through the various readings we found

that the use of tests actually is a key factor in helping information to be

stored in the memory. The process of having to retrieve information

through a form of testing makes it more recallable in the future. We also

found that frequent testing has more beneficial effects than subsequent

restudying of a topic. In fact Roediger and Karpicke (2006) found that in

one study, students remembered 61% of information from repeated retesting,

compared to 40% from repeated study.

What we didn't want to do though is

create lessons of monotony with lessons crammed with exam question

after exam question. Instead we created opportunities and methods of

testing throughout the curriculum with various levels of pressure. We

therefore designed these four opportunities:

Low stakes testing - In the testing column on the overview we spaced out (with

increasing gaps) times when we ask our teachers to test old topics. These

tests are low stakes tests but force students to retrieve information. We

created a list of ideas including ‘Write down as many things as you can about

topic x’ or ‘Challenge your partner, who can remember the most keywords from

Unit Y’ to ‘Mindmap/Spider diagram all the links between topic A and B’.

The guidance we gave teachers is that these tests must be done in the allocated

lessons and must last no longer than 5-10 minutes. They can be done as

bell work, a starter activity or even at the end of a lesson. Providing

answers should be quick and would be better if they could be done simply on one

Power Point slide. Students are now used to them as a sportsmen/women,

enjoy the challenge and friendly competition.

Unit tests –

Originally with our blocking of units, we would follow up learning with an end

of unit test. That test would purely focus on information from what has

just been taught. So in a Unit 4 test you would only see questions on

topics from Unit 4. This year we are including any question from any

previously taught unit. So in a Unit 3 test, you will now see questions

from Unit 1, 2 and 3. Teachers can formatively gather a sense of how well

that unit has been learnt throughout lessons, but now also summatively see how

they are doing within the full course. Doing this allowed us to get

students to retrieve old information and again increase its strength.

Multiple choice – Bjork’s

work made reference to the benefits of multiple choice

questions as a way of building up memory strength. We now use an

increased number of multiple choice questions throughout the curriculum.

In lessons we use hinge questions as one method on a regular basis. We do

this because if they are carefully crafted, the process that students take to

work out correct and incorrect responses helps improve retention. What we

do with these though is follow up responses. It could be easy for a

student to simply indicate an answer with no thought. We therefore create

discussions or opportunities for students to verbalise their answer, even if it

is incorrect.

Pre-tests – Based

on Bjork’s work we now run pre-tests at the very start of each unit.

These take the form of multiple choice and last no longer than 10 minutes so

curriculum time lost is very minimal. The process provides cues and is

thought to improve subsequent learning. It also helps teachers gain a

very quick insight into students prior understanding.

5 – Problem solving

In the first chapter in ‘Why Don’t Students Like

School? Willingham explains that the brain

spends a lot of this time helping us not to think. Instead it prefers to

do things automatically. But, Willingham states that it does like to

solve problems. It is naturally curious. It

doesn't necessarily mean questions but we found this

quite effective for us. We therefore ensured that during each unit

we mapped out larger driving questions. For instance, in Unit 3, students

were presented with the thought:

“What factors do athletes need to focus on in order to reach and maintain a suitable fitness level for their sport?”

This was shared in the first

lesson and everything that we subsequently learned built up a stronger ability

to answer that question. The question also allows us to tell a story

about particular aspects of sport and make the various connections between

topics.

To finish

What we haven’t done is created a

robotic curriculum design. We aren't constricted by what we have read or

learnt. The field of cognitive science is still not totally certain about

all of its claims. What we have simply done is taken the opportunity

to use research to embed 5 simple principles that may help improve longer term

retention of information. Many of these changes are at the overview level

so don’t put pressure on teachers to teach differently or in a set way.

It has simply allowed us to logistically map out key points throughout the year

which we can focus on building memory strength. There are no tips or

tricks being used in lessons (unless staff wish to do so). Instead we are

using cognitive approaches to work hand in hand with learning to make it longer

lasting.

In the next post I will look at

how we designed our curriculum to improve levels of writing, the impact of

feedback and the levels of stretch and challenge (with an A level twist!).

Resources (Click to download)

Pedagoo London 2014 presentation about our curriculum.

Copy of the curriculum overview.

Example of pre test.

Pedagoo London 2014 presentation about our curriculum.

Copy of the curriculum overview.

Example of pre test.